Empathy lies at the heart of effective leadership, serving as the bridge that connects leaders with their team members on a deeply human level. In this article, we’ll explore the indispensable relationship between genuine leadership and empathy, drawing upon the principles outlined in the empathy wheel.

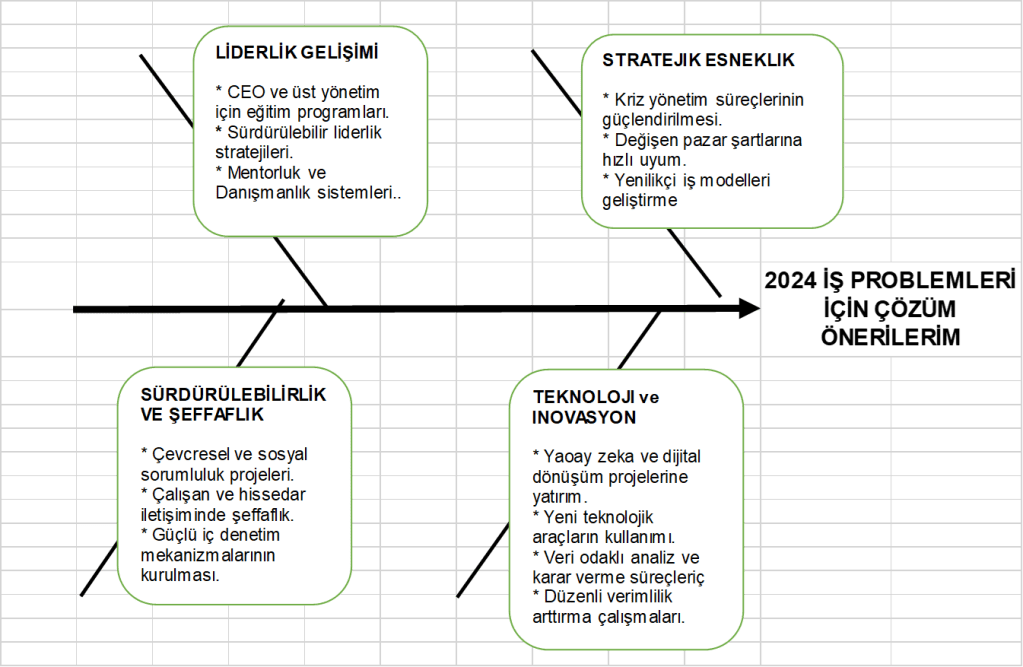

Observation: True leaders begin their journey by keenly observing the emotional states of those around them. They pay attention to both verbal and nonverbal cues, understanding that effective communication extends beyond mere words. By observing, leaders create a foundation of awareness, fostering an environment where individuals feel seen and valued.

Tune-In: Tuning in is the art of active listening—a skill that distinguishes great leaders from merely good ones. Leaders who tune in engage with their team members wholeheartedly, seeking to understand not just what is said, but the emotions underlying the message. Through attentive listening, leaders create a safe space for open dialogue and authentic expression, building trust and rapport within the team.

Relate: Leadership flourishes when leaders can relate to the experiences and emotions of their team members. By drawing parallels between their own experiences and those of others, leaders cultivate empathy from a place of shared humanity. This ability to relate fosters a sense of connection and solidarity, strengthening the bonds between leader and team.

Connect: Connection is the pinnacle of leadership—an intimate moment where leaders step into the shoes of their team members and share in their feelings. Through genuine connection, leaders validate the experiences of their team members, fostering a culture of understanding and support. This deep sense of connection inspires loyalty and commitment, driving individuals to work together towards common goals.

Reach Out: Leadership is not just about understanding—it’s about taking action. True leaders reach out to their team members with acts of compassion and support, demonstrating their commitment to their well-being. Whether through a kind word, a listening ear, or a helping hand, every act of empathy strengthens the bonds of leadership, creating a culture of trust, respect, and collaboration.

In conclusion, empathy is the cornerstone of effective leadership, guiding leaders on a journey of understanding, connection, and compassion. By embracing the principles of observation, tuning in, relating, connecting, and reaching out, leaders create environments where individuals thrive and teams flourish. In a world that craves authenticity and human connection, empathy remains the most powerful tool in a leader’s arsenal, transforming organizations and inspiring positive change.

Navigating Challenges with Empathy: In times of adversity and uncertainty, empathy emerges as a guiding light for effective leadership. True leaders understand that challenges are not just logistical hurdles but emotional journeys for their team members. By embracing empathy, leaders navigate these challenges with grace and compassion, providing much-needed support and understanding along the way. Whether it’s a setback, a conflict, or a period of change, leaders who lead with empathy inspire resilience and foster a sense of unity within their teams.

Empathy as a Catalyst for Innovation: Empathy isn’t just about understanding; it’s also about innovation. Leaders who empathize with their team members gain unique insights into their perspectives, needs, and aspirations. This deep understanding fuels creativity and innovation, as leaders are better equipped to identify opportunities for growth and improvement. By fostering a culture of empathy, leaders cultivate an environment where individuals feel empowered to share their ideas and take risks, driving organizational innovation and success.

Empathy in Diversity and Inclusion: In today’s diverse and multicultural workplaces, empathy plays a crucial role in promoting diversity and inclusion. True leaders recognize the value of different perspectives and experiences, and they strive to create environments where every voice is heard and respected. By embracing empathy, leaders foster a sense of belonging and acceptance, empowering individuals from all backgrounds to contribute their unique talents and insights. This commitment to empathy not only strengthens teams but also drives innovation and enhances organizational performance.

Empathy Beyond the Workplace: Finally, the impact of empathy extends far beyond the confines of the workplace. True leaders understand the importance of empathy in their interactions with clients, customers, and the broader community. By leading with empathy, leaders build trust, loyalty, and goodwill, enhancing the organization’s reputation and fostering long-term relationships. Whether it’s through corporate social responsibility initiatives or acts of kindness in everyday interactions, leaders who prioritize empathy leave a lasting legacy of positive change and impact.

In essence, empathy is not just a leadership trait; it’s a way of life. Leaders who embrace empathy inspire trust, foster connection, and drive positive change in their organizations and communities. As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, let us remember that empathy remains our most powerful tool for building a brighter, more compassionate future.

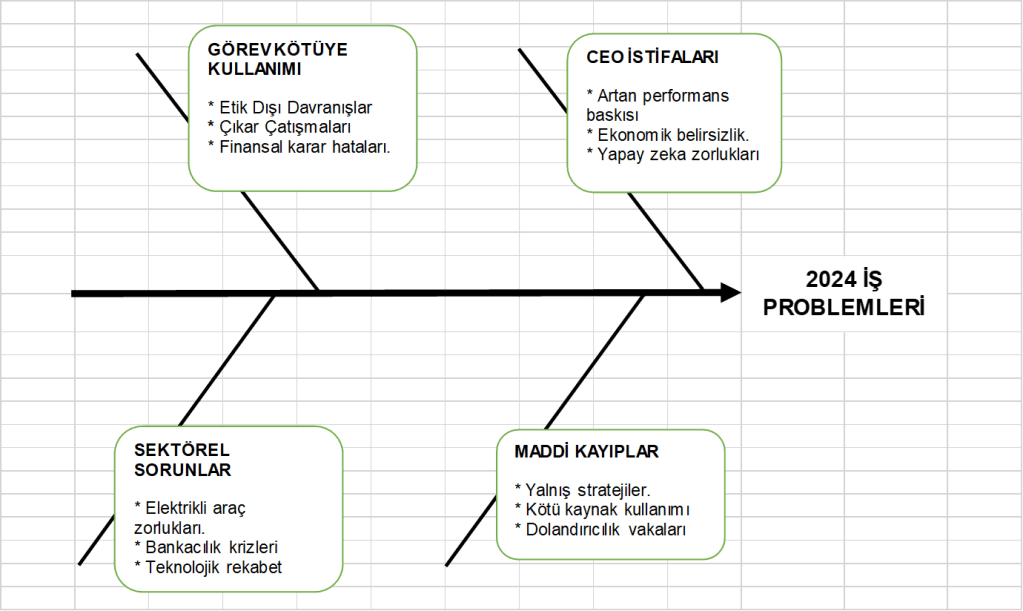

The Consequences of Empathy Deficiency: Failure to practice empathy can have detrimental effects on both individuals and organizations, leading to a host of negative outcomes. Here are some examples illustrating the consequences of empathy deficiency:

- Reduced Morale and Engagement: When leaders fail to empathize with their team members, morale and engagement suffer. Employees may feel undervalued, misunderstood, or unappreciated, leading to decreased motivation and productivity. Without a sense of connection and support from their leaders, individuals may become disengaged and disenchanted with their work, ultimately impacting the overall success of the organization.

- Increased Conflict and Miscommunication: Empathy deficiency often breeds misunderstanding and conflict within teams. Without the ability to empathize with others’ perspectives and emotions, leaders may misinterpret their team members’ intentions or dismiss their concerns altogether. This lack of understanding can escalate tensions, leading to friction, resentment, and ultimately, decreased collaboration and cohesion within the team.

- Poor Decision-Making and Innovation: Leaders who lack empathy may struggle to make informed and inclusive decisions. Without considering the diverse perspectives and needs of their team members, leaders may overlook valuable insights or fail to address critical issues. This narrow-minded approach stifles creativity and innovation, hindering the organization’s ability to adapt and thrive in an ever-changing landscape.

- Erosion of Trust and Loyalty: Empathy deficiency erodes trust and loyalty between leaders and their team members. When individuals feel that their leaders are indifferent to their needs or emotions, they are less likely to trust their judgment or follow their guidance. This breakdown in trust can have far-reaching consequences, impacting employee retention, customer satisfaction, and the organization’s overall reputation.

- Missed Opportunities for Growth and Development: Finally, a lack of empathy deprives leaders of valuable opportunities for personal and professional growth. By failing to understand and connect with their team members, leaders miss out on valuable feedback, insights, and learning experiences. This stagnation not only hinders the leader’s own development but also limits the potential growth and success of the entire organization.

In conclusion, empathy deficiency poses significant risks to individuals, teams, and organizations alike. Leaders who neglect empathy undermine morale, fuel conflict, impede innovation, erode trust, and miss out on valuable opportunities for growth. As such, cultivating empathy is not just a leadership skill—it’s a fundamental necessity for fostering a positive and inclusive work culture where individuals thrive and organizations flourish.

“I also want to include the contribution made by my friend, philosophy teacher Levent Akay, on this topic.

In today’s world, the alienation and loneliness among people are especially desired phenomena… An entity that facilitates the easier management of this crowd is the capitalist logic, especially led by figures like Bernays, and the architects of the modern consumer society who desire the consumption of the individual…

You might ask what this has to do with empathy or with good governance and leadership… Let me explain:

While there are dozens of different philosophical movements in the history of world philosophy, the turning point that shaped human life began when Marx, together with his comrade Engels, wrote Das Kapital in England… While there was actually only the conflict between two classes, and the main problem was to share the abundance gained through labor, a multitude of different ideologies and movements were created with the aim of dividing people on different views and alienating them from each other… However, until that period, we saw that people who entered into a movement with collective consciousness, managed to establish empathy and solidarity within the organized movement because they succeeded in being one and whole together…

Furthermore, due to the system, although everyone is expected to work together in the same workplace and environment, it is still impossible for anyone to establish empathy in the work environment triggered by the natural ambitions of rising within the system and different material and status opportunities, because, by nature, everyone deserves everything first and foremost, which creates an environment where years of effort and sacrifice become worthless and causes people to drift apart, and even prevents leaders, who should guide the next generation with their knowledge and experience, from passing on these qualities, because what matters to a capitalist employer is less expense and more profit…

Therefore, with the hope of living in a world dominated by a social logic where empathy along with unity and solidarity prevail, I wish you all a Happy International Workers’ Day… I congratulate all workers. “

Yes, I am a romantic Socialist.